(Text in French / Version française de cette page : ![]() )

)

You will find here the replies to the most frequently asked questions:

· How has this database been made up?

· What data is available?

· Is the database complete?

· How is the data distributed over the whole territory?

· How do I find out more about a particular individual?

How has this database been made up? By whom?

An understanding of the historical context is necessary before replying to this question.

The British authorities quickly realised the crucial importance of their fighter pilots and bomber crews. There were only a few of them and their training was long and expensive. Many of them would be taken prisoner or killed in combat but other more fortunate ones would escape capture after landing in enemy territory.

In 1939 the War Office created M.I.9, a secret organisation to help captured airmen to escape. Those who did get away would be called « Escapers ». The other purpose of M.I.9 was to help airmen who had parachuted into enemy territory to get back to England. These were called « Evaders ». In December 1941, the United States entered the war and in October 1942, created an organisation similar to the English model: MIS-X, based at Fort Hunt, in Virginia. The objectives were the same and the two organisations worked closely together with an MIS-X office established in London whose main objective was to interrogate American airmen who succeeded in getting back to England.

Escape reports written on the airmen’s return to London often contained useful intelligence information (enemy troop positions, infrastructures and so on) and sometimes provided precious details which helped subsequent airmen to escape capture. The experiences of the first airmen would serve those that followed. These reports often contained the names of people who had helped them in their escape effort but the information was often incomplete, and the spelling of French names sometimes imagined. For reasons of security, it was preferable that the airmen did not know the real names of people helping him, in case they were captured.

After the war, the offices MI9 and MIS-X were closed down. The Allied authorities nevertheless wished to find - and sometimes remunerate - people who had helped their airmen. New temporary bureaus were established in the countries concerned (in France from the autumn of 1944) and they worked in collaboration with the national intelligence services. In order to find the Helpers, the officers had the escape reports and they made it known in the press that an investigating bureau existed in order to register all those who had helped, in any way whatsoever.

Each case had an individual file, from a few pages for the simplest, to more than a hundred pages for the more complex. The first objective was to verify the facts: did the evidence agree with the reports of the evader that the person is said to have helped? Did the dates coincide? In the case of the person having been deported for having helped an Allied airman, the bureau could give financial compensation. This was also the case for the widows or families of those who had been shot or died in deportation. A pension might be awarded as a function of several factors, including the number and age of any dependent children. Financial compensation might also be given to those who had spent their own money in supporting the evaders they had sheltered.

At the end of this huge task of registering and verification, a « grade » from 1 to 5 was given to each person (see later), although the Americans and English had slightly different systems. A letter of recognition or an official certificate often accompanied locally organised ceremonies to pay tribute to those who had taken enormous personal risks, and often paid a very high price …

Finally, a general index was produced to make research easier. This re-grouped all the names of those who had given help, either confirmed or not, in alphabetical order. This general index can be found in the English National Archives at Kew, and a copy exists in the American National Archives at College Park, Maryland. For France, the general index is more than 1,500 pages long with a total of 20,000 files. A file can include a single individual, a couple or sometimes an entire family.

In 2012, the 1,500 pages of this index were photographed at the archives in Kew by John Howes. Bruce Bolinger then put them on his website in 2013 (cf. Links). I have to thank Bruce for giving me permission to use this data to make up a database. All that remained was the work needed to make up an indexed and geo-localised database, a job which was undertaken in 2014 and 2015.

Which data is available in the « Register of Helpers »?

The paper index is organised in seven sections, which make up as many columns which can be found on all the pages of the register.

1. "Helper's name"

This is simply the title, family name and first name of the person or persons concerned. The surname is always written in capitals and appears before the first name. For a couple, it is usually only the name of the husband that appears, but there are numerous exceptions. The index specifies the first name and sometimes the other first names (middle names) of the person. There are no particular rules, and the degree of accuracy of the marital situation varies from one file to another.

For the medical professions, the title used is in general « Dr »or « « Dr & Mme » for a married couple. There are about 400 doctors on this list.

The men and women of the church are given the title “Father, Priest, Rev, Abbot or Vicar” (in French) for men and « Sister or Mother » for women. More than 200 files concern members of the church.

For military personnel, the rank is used. This means, of course the rank held at the time of registering after the war. From an ordinary corporal to a general, there are 250 military files.

Nobility is also represented in the files « Duke, Baron, Count, Marquis and Prince » with their feminine equivalents. The database contains about one hundred files of French, and sometimes foreign, nobility.

Note that sometimes the spelling of family names is wrong, notably for the more complex.

2. « Helper’s address »

This section gives the address of the person. For small towns and villages, it is not unusual for only the name of the commune, and not the complete address, to be given.

Note that the address is the last known address when the files were made up. This does not mean that the aid given to the airmen took place in the commune indicated: the person could have moved house in the meantime or have several addresses, so one has to be very careful when reconstructing the route of an evader in Occupied France. Nevertheless, moving house in the French countryside was a very infrequent event at the time. This is perhaps less true in the richer or more populated areas.

A number of errors were identified and corrected during the creation of the database. These errors can be explained by the lack of knowledge of French territory on the part of the people who made up these files. Also, since the end of the war, many of the communes have disappeared (perhaps merged with a neighbouring large town), changed their name, or become associated with a neighbouring commune and the two names combined. Because of the geo-localisation used for this database, the official names of the communes in 2015 have been used, rather than the name at the time. This rule applies similarly to the departements, whose structure has also evolved since the war.

The address (street and number) is shown in some entries of the present version of the database. The spelling in the index is often wrong and many of the streets have changed their names since the war, which does not help when trying to find the exact places of abode in many cases. The profession is sometimes indicated. When it is shown, it is often in English.

The profession is partially found in the database.

3. “Award grade proposed”

This section specifies the grade proposed by the Allied authorities, according to a scale of 1 to 5.

This section specifies the grade proposed by the Allied authorities, using a scale of 1 to 5.

Level 1 was accorded to those who ran escape networks and/or helped several dozen evaders. Grade 5 was the most common and was accorded to those who provided timely but significant help to one or two Allied evaders.

The website evasioncomete.org has a page dedicated to this question.

Information on grades is not included on the database.

4."Certificate Number" / 5. "Compensation paid" / 6. "Claim Number"

When a file is deposited, a unique claim number is generated. Its presence is not systematic, and the motives of presence/absence of such a number are not known.

When a file has been validated and approved, a certificate number is attached to the file. The exact procedure for generating these numbers is not known.

In some specific cases, help given to the Allies was the subject of financial compensation from a budget shared between the English and the Americans (as a function of the nationality of the evaders who were helped).The largest sums were generally given to the widows/widowers of those who lost their lives as a direct result of having helped Allied evaders.

7. "Remarks"

This last section, when applicable, indicates the circumstances - often tragic - associated with a file such as deportation, died in deportation, beaten up, imprisoned etc …

The note « US only » signifies that the file concerns only an airman (or a group of airmen) of the US Army Air Force. These files were treated slightly differently from the English or mixed files.

The note « No confirmation » signifies that the help given has not been verified by the competent authorities. Very often, this means names which have been written in the escape reports or the files of other Helpers, but who have not been able to be contacted and verified. The author of this site made the choice of including the details of persons whose action has not been confirmed in the database.

The addition of this information in the database happens on a case by case basis.

Is the database complete ?

In spite of the enormous effort produced by the Allies at the end of the war to register all the Helpers it is evident that there are names missing from this list. In the same way, one can imagine that certain persons « exaggerated » the help which they gave, and because of this, are less worthy than others who did not even make themselves known.

Whatever, the present list is the most complete ever produced, and gives a solid base from which the researcher can work.

The American National Archives have another nominative list, and many of the names on this list do not figure in the English register. This list is available at www.Archives.gov

Do not hesitate to contact the author of this site if you wish to rectify some of its contents.

How do we explain the distribution over French territory?

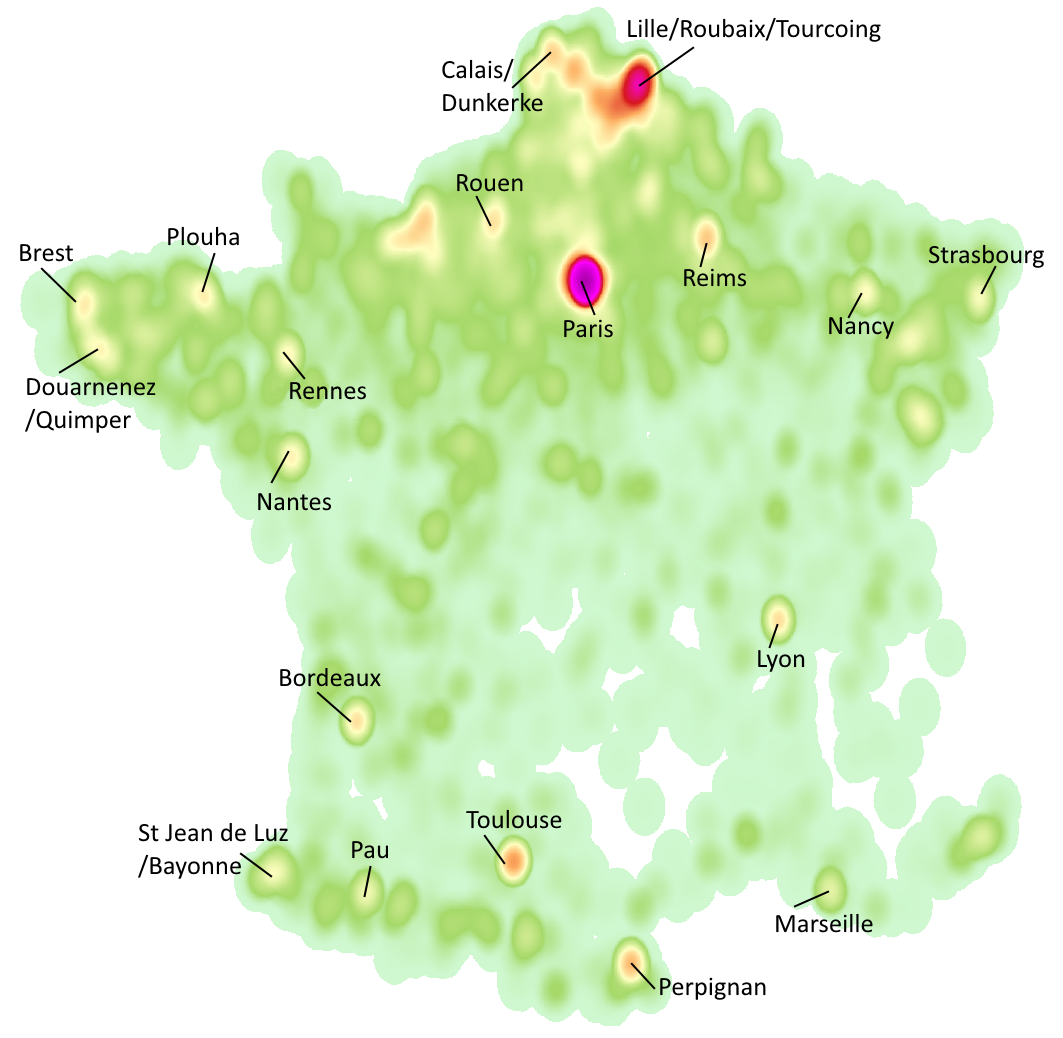

The map below shows the average « density » of help given to the Allies. The numbers are calculated taking into account the geographic position of each town registered, and the number of Helpers whose address corresponds to this town.

The areas with the greatest density of helpers are shown in yellow/orange/red/violet and the less dense areas in green. The absence of any representation is shown by a white area, as in the case of most of the Massif Central and the Alps.

It is of course a very static view, which does not show the complex evolution of movements and help for the Allies which was in its infancy in 1940, and very organised by the end of the conflict. However, it sheds an interesting light on the history, visually illustrating some of the characteristics which favoured the emergence of Helpers in such and such a region.

North/South inequality

The evidence shows that there were many more Helpers in the northern half of the country. This is easily explained: between 1939 and 1945 many more aircraft crashed in the northern half of France, and notably in the regions Nord/Picardie/Normandy/Champagne Ardennes and Brittany. This is because so many of the aircraft which took off from England to bomb Germany flew over the northern half of France, and so risked being shot down over French territory. Added to that are the crashes of aircraft whose targets were situated in France itself, such as the Atlantic ports, strategic targets on the transport network, and the bombings prior to the Normandy invasion.

Aircraft crash and parachutes are deployed. People come to their aid. « Spontaneous » help appears near the crash sites but it does not explain the large number of Helpers in the bigger towns.

Big towns

Despite numerous German troops and Gestapo personnel in the larger conurbations, the anonymity of the large towns is a trump card for those who bring help to the airmen. An unrecognised face is much less suspect here than in a small village where everyone knows each other.

Hosts (logeurs/logeuses), guides (convoyeurs/convoyeuses) and many other members of the organised escape networks, some of whom numbered in the hundreds, generally lived in the cities. However, the anonymity of towns did not prevent numerous arrests and deportations among the networks, many of which had been infiltrated by agents whose specific role was to dismantle them.

Paris was different. More than 2,400 Helpers were registered as being in the capital! It should be noted that Paris was on the route of a many of the escape lines which used the rail network to evacuate airmen. Paris was a particularly important stage on those lines which ran from the north of Europe to the Pyrenees.

To a lesser extent, Lyon, Marseille, Toulouse and Bordeaux were also points on several networks.

The North

After Paris and its suburbs, the northern regions are the most represented, and they combine several of the factors already mentioned, especially the large number of aircraft shot down in the area, and also hundreds of British soldiers escaping in June 1940. The region around Lille also accrued many families who sheltered escapers and evaders coming from Belgium and Holland, and who, in spite of the geographic closeness of the English coast, were limited to passing into France with the intention of getting to Spain - and sometimes Brittany – in order to get back to England.

The Barrier of The Pyrenees

The map also shows great activity in the area separating France and Spain. Many passeurs and hosts were needed to take the airmen into Spain, whose relative neutrality offered them access – although sometimes complicated - to Gibraltar, the British enclave which Franco had never wanted to give up to the Germans.

In the west, Biarritz and St Jean–de-Luz were important staging points. The routes which cross the Pyrenees were not a stroll in the park for these men who, tired and badly prepared, often faced several days of walking on these secret and dangerous paths.

In the east, it was Perpignan and its surrounding area which welcomed the evaders who went on to cross the Spanish border. They usually came from Toulouse or Marseille.

Brittany

The skies over Brittany saw the passage of many American bombers. One escape network took evading airmen to the northern coast of Brittany, and evacuated more than a hundred of them. The region around Plouha, from where they left by boat, is highly represented (along with the neighbouring towns of Saint-Quay-Portrieux and Saint-Brieux), and is shown clearly on the map.

How do we find out more about a person figuring in the index ?

The general index is only a drop in the ocean of the mass of documents which the American National Archives (NARA) hold on the French Helpers.

If a name is listed in the general index, then there is a good chance that a personal file with that name is available in one of the 300 boxes of archives of individual files held at College Park. The probability that a file exists for those « not confirmed » is far less.

Individual files are made up of several pages, and sizes vary considerably from a few pages for the simpler files, to more than a hundred for the more complex. The same file may include several people (usually couples and families).

Note that even files linked solely to British escapers and evaders are kept in the American archives.

What do these files contain?

Here we find all the documents collected, not necessarily chronologically, in the construction of the file. These documents consist of:

- Correspondence between the subject and the American authorities

- standardised questionnaires, often annotated with elements of verification

- financial elements (sometimes)

- elements of evaluation of the rank used in the file

- documents linked to the award of a diploma or certificate

- photos (only fairly rarely)

In the majority of cases these documents contain information about the airman or airmen who have been helped by the person in question, with the details allowing the researcher to « reconstruct » (at least part of) the route of the airmen. The date and duration of the lodging, the persons through whom, and towards whom, the airman has been led, etc, are often included.

On reading these files, it is essential to bear in mind the context in which they were produced: we are in the after-war period and the conditions of life for the majority of French people are difficult. Sometimes the files are the object of financial stakes, and in some of them one can find a slightly deformed reality, notably where the duration of stay is concerned. There are however few of these cases, and many Helpers refused all material help, even when they had spent their own money to feed and lodge the airmen.

The notes of the authorities show that what was said was not taken at face value. Verifications were made by comparing with other documentary sources (notably escape reports). The names of airmen mentioned were identified and the dates checked so as to find eventual suspect rescues etc. The amount of work that this verification process produced was tremendous, considering the number of files to be looked at.

It must be noted that certain persons were « Black-listed » after studying their file, even if they had effectively helped an airman: for example, a too shady past, proven denunciations of other helpers etc.

In almost every case, the files contain information not found elsewhere, and which was sometimes not even known to the descendants of the Helpers represented.

How do we get access to these files?

This is where things get complicated. The Helper files are not directly accessible on the internet. According to NARA, a computerised project is being studied but no dates have been announced as to when these documents might be available on their website. Do not hesitate to contact the author of this site to learn about the different ways of accessing one or several of these files.

LineBreakSM: No

LineBreakMD: No

LineBreakLG: No